My recent posts on my own family photos reminded me of a vintage photo album I bought in a thrift shop a decade or so back. I loved the "period" look of it--the black pages annotated with white ink, the traditional photo corners, the textured cover. I was amazed to see that virtually all of its several hundred photos were intact. And yes, being the sentimental crazy woman I am, I was saddened by it. Here was the history of an entire personal and family life, lovingly created, a small treasure but one that is both complex and precious...left to languish on a shelf with a ten dollar price tag. Naturally, I could do nothing other but scoop it up for "adoption."

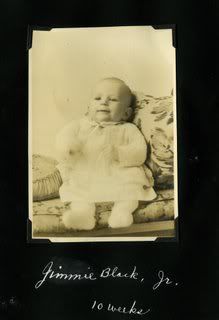

My photo-expert pal CJ scanned the images and also some of the actual pages for a project we did several years ago; I've added one of those scans to this post. As it shows, this photo-owner did caption her photos, and in a graceful handwriting few of us today can match. I've sometimes said that I'm going to do a web search and see if I can find the descendents of some of the names in the book. So far, though, I haven't done much more than browse the album, use some of the pictures in art and blog posts, and simply enjoy it all.

And that enjoyment is the paradox of my ownership of this piece of ephemera. The family pictured in the album might not have valued it, or perhaps they just didn't know it was there for the asking. But I, a complete stranger, love it. I remember its dogs, its houses, its trips to beaches and lakeside cabins. To me it is precious in part because of its mystery. It isn't my family; it's the human family. Maybe that's why I never quite get around to searching for the families it pictures. Maybe it reverberates all the more because of what it doesn't say.

Showing posts with label photography. Show all posts

Showing posts with label photography. Show all posts

Saturday, October 9, 2010

Wednesday, September 8, 2010

PHOTOGRAPHS, past and present

To give myself some respite from the computer, I spent some of Labor Day weekend sorting through photographs of my late mom and dad. My friend and colleague CJ Madigan is going to create small books from them using her new Snapshot Stories format (I'm a test subject; watch her web site for its introduction later this fall, and this blog for a peek at my books when completed.)

Looking through old photos is a mixed blessing once you've lost close loved ones. The sight of their faces in a picture is bittersweet, reminding you that they are no longer here yet at the same time recalling happy times together. My own photo "shoebox" had scores of wonderful shots, an abundance that made choosing among them difficult.

Today, most everyone has that same kind of overstuffed shoebox (or album, or drawer). The most obvious reason for this is that these days anyone can take a photo, from almost any kind of device from the most elaborate camera to the simplest cell phone. Anyone can print that photo, too, at least anyone who has access to a drugstore photo lab or a home computer. How different this is from my childhood, when developing a negative required both expertise and a special room full of expensive equipment, much less from the early days of photography when the camera, too, was expensive and difficult to use.

But it's not just technical issues that allow us to take photographs for granted today. We also enjoy long life expectancies and relatively easy, relatively affordable travel. It's fairly easy, most of the time at least, to see the people we have photographs of. The exact opposite was true in the early days of photography. Travel was dangerous and expensive; families that were separated might not see each other for years, if ever. Death was an everyday fact of life, taking away everyone from infants to children to mothers and on. The rich could afford portraits of those from whom either death or other circumstance had separated them, but others could not.

And so a photograph was not just a pleasure, but a prize. Here is Jane Welsh Carlyle, the wife of celebrated author and intellectual Thomas Carlyle, writing on the subject in 1860: "Blessed be the inventor of photography! I set him above even the inventor of chloroform! It has given more positive pleasure to poor suffering humanity than anything else that has cast up in my time or is like to—this art by which even the poor can possess themselves of tolerable likenesses of their absent dear ones."

That reference to chloroform is worth noting; it wasn't one that was made lightly. Ether and chloroform, the first general anesthetics, were still relatively new in 1860 (Queen Victoria, for example, had not used one until the birth of her eighth child in 1853). To set photography above chloroform, a substance that relieved horrendous labor or surgical pain, was to praise it highly indeed.

So while culling down my pile of "possible" photos was a chore, I tried not to forget that it was also a privilege. We are indeed lucky today, not just to have the luxury of easy photography (and easy book-making services like CJ's) but also to have the blessing of the long and healthy lives that let us enjoy each other in person.

Looking through old photos is a mixed blessing once you've lost close loved ones. The sight of their faces in a picture is bittersweet, reminding you that they are no longer here yet at the same time recalling happy times together. My own photo "shoebox" had scores of wonderful shots, an abundance that made choosing among them difficult.

Today, most everyone has that same kind of overstuffed shoebox (or album, or drawer). The most obvious reason for this is that these days anyone can take a photo, from almost any kind of device from the most elaborate camera to the simplest cell phone. Anyone can print that photo, too, at least anyone who has access to a drugstore photo lab or a home computer. How different this is from my childhood, when developing a negative required both expertise and a special room full of expensive equipment, much less from the early days of photography when the camera, too, was expensive and difficult to use.

But it's not just technical issues that allow us to take photographs for granted today. We also enjoy long life expectancies and relatively easy, relatively affordable travel. It's fairly easy, most of the time at least, to see the people we have photographs of. The exact opposite was true in the early days of photography. Travel was dangerous and expensive; families that were separated might not see each other for years, if ever. Death was an everyday fact of life, taking away everyone from infants to children to mothers and on. The rich could afford portraits of those from whom either death or other circumstance had separated them, but others could not.

And so a photograph was not just a pleasure, but a prize. Here is Jane Welsh Carlyle, the wife of celebrated author and intellectual Thomas Carlyle, writing on the subject in 1860: "Blessed be the inventor of photography! I set him above even the inventor of chloroform! It has given more positive pleasure to poor suffering humanity than anything else that has cast up in my time or is like to—this art by which even the poor can possess themselves of tolerable likenesses of their absent dear ones."

That reference to chloroform is worth noting; it wasn't one that was made lightly. Ether and chloroform, the first general anesthetics, were still relatively new in 1860 (Queen Victoria, for example, had not used one until the birth of her eighth child in 1853). To set photography above chloroform, a substance that relieved horrendous labor or surgical pain, was to praise it highly indeed.

So while culling down my pile of "possible" photos was a chore, I tried not to forget that it was also a privilege. We are indeed lucky today, not just to have the luxury of easy photography (and easy book-making services like CJ's) but also to have the blessing of the long and healthy lives that let us enjoy each other in person.

Wednesday, June 9, 2010

ON A PLAYFUL NOTE: furniture, forlorn

This post isn't really meant for you if you're recently bereaved. One's delight in the ridiculous usually takes a while to come back. But it may make you smile if you're somewhere past the absolute worst.

I came across Bill Keaggy's little book Fifty Sad Chairs about a year after my father died. Each of its 4-inch square pages offers a photo of a real chair abandoned in a real place somewhere in St. Louis and photographed exactly as found. A single look at the photos was enough to make me laugh out loud. Keaggy's sad chairs were so sad, so deeply forlorn, so put-upon, so down and out they made the entire concept of sadness feel amusing. Keaggy's brief introduction notes, "You'll see them beside dumpsters, in backyards, in vacant lots and on the sidewalk. These are the forsaken chairs...They saved us from having to sit on the floor. And how do we repay them? With a grunt, a curse, and a heave-ho to the street." If these chairs were characters in Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh, they'd all be Eeyore: depressed, desultory, and deeply under-appreciated.

The image I reprint here is titled "She Never Calls Anymore." It was taken sometime before 2007, when the book was published. Today, not only the chair is gone, but probably the phone booth too. I wonder if Keaggy would consider a book called Fifty Forlorn Phones.

I came across Bill Keaggy's little book Fifty Sad Chairs about a year after my father died. Each of its 4-inch square pages offers a photo of a real chair abandoned in a real place somewhere in St. Louis and photographed exactly as found. A single look at the photos was enough to make me laugh out loud. Keaggy's sad chairs were so sad, so deeply forlorn, so put-upon, so down and out they made the entire concept of sadness feel amusing. Keaggy's brief introduction notes, "You'll see them beside dumpsters, in backyards, in vacant lots and on the sidewalk. These are the forsaken chairs...They saved us from having to sit on the floor. And how do we repay them? With a grunt, a curse, and a heave-ho to the street." If these chairs were characters in Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh, they'd all be Eeyore: depressed, desultory, and deeply under-appreciated.

The image I reprint here is titled "She Never Calls Anymore." It was taken sometime before 2007, when the book was published. Today, not only the chair is gone, but probably the phone booth too. I wonder if Keaggy would consider a book called Fifty Forlorn Phones.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)